Humayun had reconquered India in 1555 with the help of the Shia ruler of Iran, Shah Tahmasp (r. 1658–1707) signify a preoccupation with portraiture in manuscript art.Īkbar ascended the throne in 1556 at the age of 13, after the untimely death of his father, Humayun (r. The hundreds of portrait images of Akbar that were illustrated during his reign and during the reigns of his successors Jahangir (r. Portraiture-that is, images of persons drawn from life-was introduced into manuscript art 8 in India during the reign of Emperor Akbar. Significance of Portraiture in Mughal Manuscript Art By raising these questions, I wish to trace how portraiture became a political tool for stating the ideology and sovereignty of Mughal emperors. These questions are relevant to my research on the portrait of Akbar, which occupies a significant position in the genre of portraiture, explored extensively during the reign of Akbar and his successors. Were there any differences between the portrait of Akbar illustrated during his reign and posthumous images illustrated during the reign of his son and successor, Jahangir (r. Which transcultural prototypes helped shape the portrait image of Emperor Akbar in the painted folios of the Akbarnama?ģ.

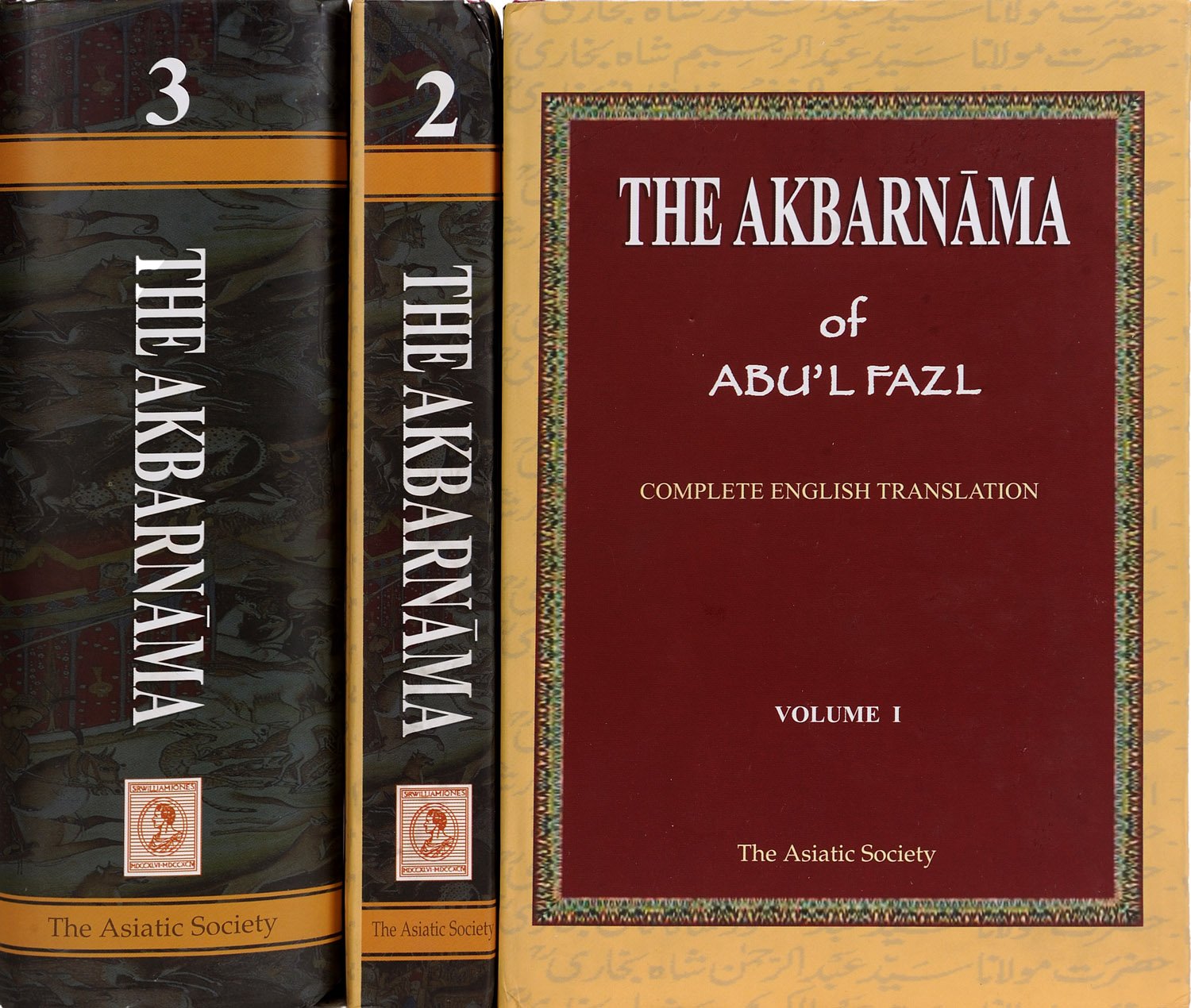

What was the significance of portraiture during the reign of Emperor Akbar?Ģ. In this paper, I raise three questions about the portrait of Akbar in the Akbarnama and attempt to answer them through my research.ġ. 7 The text written by Abul Fazl was further produced into illustrated manuscripts, documenting pictorially the important episodes in the life and reign of Emperor Akbar. Abul Fazl took several years to complete it, finally presenting the Akbarnama (Book of Akbar) to the emperor in 1579. Akbar also ordered the history of his own reign to be chronicled, and Abul Fazl was chosen to write it.

These illustrated manuscripts contained portrait images of Timurid and Mughal ancestors based on textual descriptions available in the writings of Timurid princes, including Babur, 6 and made into stunning folios by the imperial artists. Along with Persian epics, Akbar had the reigns of his ancestors written and compiled into histories, several copies of which he ordered to be produced into magnificent manuscripts. 5 The subjects explored in the manuscripts were primarily Persian texts authored by medieval poets such as Firdausi, Nizami, and Jami.

During Akbar’s reign, hundreds of thousands of folios were produced (for assembling into albums and manuscripts) in the imperial atelier by an estimated 100 artists working together as a team. The portraits included Turko-Mongol ancestors of Akbar who ruled in central Asia during the Timurid dynasty (1350–1507) 2 Akbar’s immediate ancestors, Babur and Humayun 3 the men of Akbar’s court belonging to several different cultural and regional backgrounds 4 and Emperor Akbar himself. In the closing years of the sixteenth century in India, there was an unexpected burst of portraits of medieval Indian men drawn from life that appeared in illustrated manuscripts, patronized by the third Mughal emperor 1 Akbar (r. In this article, she explains how portraiture in the book is used to justify the sovereignty of the successors. Using an SRA award, she visited London and Dublin to see and study some of the original manuscripts of the Akbarnama, a beautiful illustrated book commissioned by a Mughal emperor. Dipanwita Donde is a 2014–15 Sylff fellow from Jawaharlal Nehru University in India.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)